From Purgatorio

Purgatorio (Italian for "Purgatory") is the second part of Dante's Divine Comedy, following the Inferno, and preceding the Paradiso. The poem was written in the early 14th century. It is an allegory telling of the climb of Dante up the Mount of Purgatory, guided by the Roman poet Virgil, except for the last four cantos at which point Beatrice takes over as Dante's guide. In the poem, Purgatory is depicted as a mountain in the Southern Hemisphere, consisting of a bottom section (Ante-Purgatory), seven levels of suffering and spiritual growth (associated with the seven deadly sins), and finally the Earthly Paradise at the top. Allegorically, the poem represents the Christian life, and in describing the climb Dante discusses the nature of sin, examples of vice and virtue, as well as moral issues in politics and in the Church. The poem outlines a theory that all sin arises from love – either perverted love directed towards others' harm, or deficient love, or the disordered love of good things.

Introduction[edit]

Having survived the depths of Hell (described in the Inferno), Dante and Virgil ascend to the Mountain of Purgatory on the far side of the world. The mountain is an island, the only land in the Southern Hemisphere. Dante describes Hell as existing underneath Jerusalem, created by the impact of Satan's fall. Mount Purgatory, on exactly the opposite side of the world, was created by a displacement of rock, caused by the same event.[1] Dante announces his intention to describe Purgatory by invoking the mythical Muses, as he did in Canto II of theInferno:

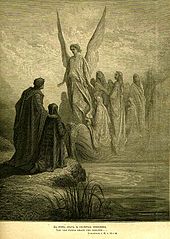

Allegorically, the Purgatorio represents the penitent Christian life.[3] In a contrast to Charon's ferry across the Acheron in the Inferno, Christian souls here arrive escorted by an angel, singing In exitu Israel de Aegypto[4] (Canto II). In his Letter to Cangrande, Dante explains that this reference to Israel leaving Egypt refers both to the redemption of Christ and to "the conversion of the soul from the sorrow and misery of sin to the state of grace."[5]Appropriately, therefore, it is Easter Sunday when Dante and Virgil arrive.[6]

The Purgatorio demonstrates the medieval knowledge of a spherical Earth.[7][8] During the poem, Dante discusses the different stars visible in the southern hemisphere, the altered position of the sun, and the various timezones of the Earth. At this stage it is, Dante says, sunset at Jerusalem, midnight on the River Ganges (with the constellation Libra overhead there), and dawn in Purgatory:

Ante-Purgatory[edit]

At the shores of Purgatory, Dante and Virgil meet Cato, a pagan who has been placed by God as the general guardian of the approach to the mountain (his symbolic significance has been much debated). On the lower slopes (designated as "Ante-Purgatory" by commentators), they also meet two main categories of souls whose penitent Christian life was delayed or deficient: the excommunicate and the late repentant. The former are detained here for a period thirty times as long as their period of contumacy. The latter includes those too lazy or too preoccupied to repent, and those who repented at the last minute without formally receiving last rites, as a result of violent deaths. These souls will be admitted to Purgatory thanks to their genuine repentance, but must wait outside for an amount of time equal to their lives on earth.

The excommunicate include Manfred of Sicily (Canto III). The lazy include Belacqua (possibly a deceased friend of Dante), whom Dante is relieved to discover here, rather than in Hell (Canto IV):

The seven terraces of Purgatory[edit]

From the gate of Purgatory, Virgil guides the pilgrim Dante through its seven terraces. These correspond to the seven deadly sins or "seven roots of sinfulness."[16] The classification of sin here is more psychological than that of the Inferno, being based on motives, rather than actions.[17] It is also drawn primarily from Christian theology, rather than from classical sources.[18] The core of the classification is based on love: the first three terraces of Purgatory relate to perverted love directed towards actual harm of others, the fourth terrace relates to deficient love (i.e. sloth or acedia), and the last three terraces relate to excessive or disordered love of good things.[16]

Each terrace purges a particular sin in an appropriate manner. Those in Purgatory can leave their circle voluntarily, but will only do so when they have corrected the flaw within themselves that led to committing that sin.

The structure of the poetic description of these terraces is more systematic than that of the Inferno,[19] and associated with each terrace are an appropriate prayer, a beatitude, and historical and mythological examples of the relevant deadly sin and of its opposite virtue.

No comments:

Post a Comment