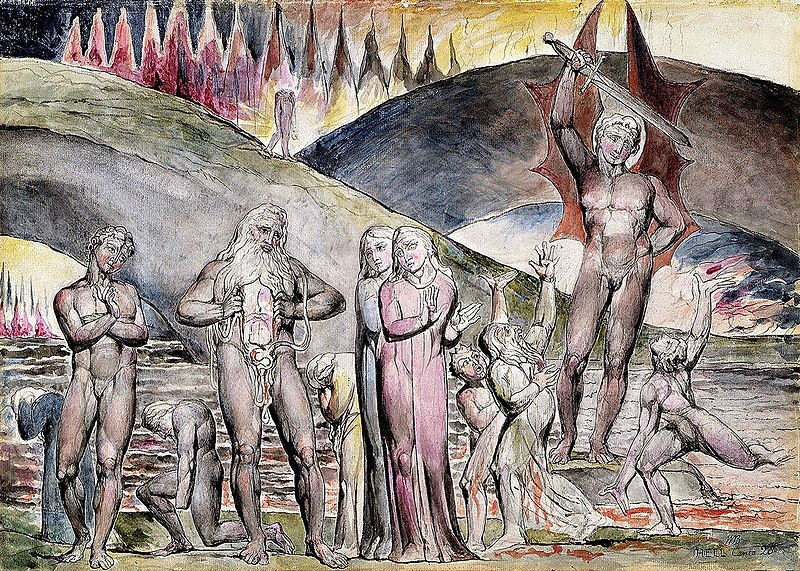

Dante Inferno XXVIII 101-135 Then did he lay his hand upon the jaw Of one of his companions, and his mouth Oped, crying: "This is he, and he speaks not. This one, being banished, every doubt submerged In Caesar by affirming the forearmed Always with detriment allowed delay." O how bewildered unto me appeared, With tongue asunder in his windpipe slit, Curio, who in speaking was so bold! And one, who both his hands dissevered had, The stumps uplifting through the murky air, So that the blood made horrible his face, Cried out: "Thou shalt remember Mosca also, Who said, alas! 'A thing done has an end!' Which was an ill seed for the Tuscan people." "And death unto thy race," thereto I added; Whence he, accumulating woe on woe, Departed, like a person sad and crazed. But I remained to look upon the crowd; And saw a thing which I should be afraid, Without some further proof, even to recount, If it were not that conscience reassures me, That good companion which emboldens man Beneath the hauberk of its feeling pure. I truly saw, and still I seem to see it, A trunk without a head walk in like manner As walked the others of the mournful herd. And by the hair it held the head dissevered, Hung from the hand in fashion of a lantern, And that upon us gazed and said: "O me!" It of itself made to itself a lamp, And they were two in one, and one in two; How that can be, He knows who so ordains it. When it was come close to the bridge's foot, It lifted high its arm with all the head, To bring more closely unto us its words, Which were: "Behold now the sore penalty, Thou, who dost breathing go the dead beholding; Behold if any be as great as this. And so that thou may carry news of me, Know that Bertram de Born am I, the same Who gave to the Young King the evil comfort. I made the father and the son rebellious; Achitophel not more with Absalom And David did with his accursed goadings. Because I parted persons so united, Parted do I now bear my brain, alas! From its beginning, which is in this trunk. Thus is observed in me the counterpoise."

The Schismatics and Sowers of Discord: Mosca de' Lamberti and Bertrand de Born 1824-27

pen, ink and watercolour over pencil (NGV 24)

Felton Bequest, 1920

1009-3

National Gallery of Victoria

This from Digital Dante:

The souls of this bolgia include disseminators of civil as well as religious discord: the contemporary Christian heretic Fra Dolcino is here, the classical Roman Curio, as well as the contemporaries Pier da Medicina, Bertran de Born, and Mosca de’ Lamberti. Mosca, who is on the list of famous Florentines citizens of the previous generation about whom Dante quizzes Ciacco back in Inferno 6, claims responsibility for having created the discord that plagues Florence (and that ruined Dante’s own life, to the extent that it was ruined by his exile).

The human shapes of these sinners are mutilated in ways that indicate their mutilation of the body politic: again, we find here the principle of the literalized metaphor discussed in the Introduction to Inferno 3. Here the metaphor is the rending of that which should be whole.

As the schismatics tore asunder the fabric of the body politic (and consider the Old Man of Crete in Inferno 14 as another literalizing of the “body politic”), so they are now themselves torn asunder. Never does Dante demonstrate more clearly—almost pedagogically—the way in which “the punishment fits the crime” (to use Gilbert and Sullivan’s expression). Hence it is perhaps not surprising that Bertran de Born, the Occitan troubadour holding his head at the end of the canto, enunciates the word “contrapasso” in Inferno 28.142, the last verse of the canto.

Bertran, a poet famous for his martial verse, whose poetry is echoed in the long and bloody similes that open the canto, fostered the division between the son Prince Henry (known by contemporaries as “the young king” or “re giovane” as Dante calls him in Inf. 28.135) and King Henry II of England, his father. Bertran explains that the sundering of son from father is reflected in the sundering of his head from his torso:

_The_Baffled_Devils_Fighting.jpg)