A valuable resource for students of Blake is the Yale Center for British Art which houses the large collection of Blake's work which

was amassed by Paul Mellon. The following passage by the Chief Curator of Art Collections at the Yale Center for British Art, Matthew

Hargraves, demonstrates that Melon's interest in accumulating

works by William Blake was influenced by his association with

Carl Jung.

From Matthew Hargraves who is Chief

Curator of Art Collections at the

Yale Center for British Art:

"[I]t was the interest of his first wife, Mary Conover Mellon,

whom he married in 1935, in thought and methods of Carl Jung that

helped transform Paul Mellon into a major collector of Blake’s

work.

Mary had introduced Paul Mellon to Jung’s ideas after they met in

late 1933; even before marriage they had begun Jungian analysis in

New York. In the early summer of 1938, Mr. and Mrs. Mellon

journeyed to Switzerland and spent several weeks in Ascona above

Lake Maggiore hoping the mountain air would relieve Mary’s chronic

asthma. By coincidence Carl Jung was also in Ascona and the couple

met the psychiatrist for the first time that summer. They returned

the following year and saw Jung again before settling in Zurich in

September 1939 to meet with Jung as patients several times a week.

Germany’s invasion of Poland in 1939 meant this Swiss idyll could

not last. In the spring of 1940 Mr. Mellon took a walking holiday

with Jung but the obvious threat from Nazi Germany could not be

ignored. He and Mary returned hastily to the United States shortly

before the occupation of Denmark, Norway and France in May. By

June 1941, feeling compelled to take action, Paul had enlisted in

the US army; December saw the Japanese attack on Pearl Harbor and

the United States enter the war.

While wartime service forced an end to the relationship with

Jung, the year Paul Mellon enlisted was also the year he began to

collect important works by Blake, an artist in whom Mr. Mellon

found new interest through Jung’s exploration of the unconscious

and his theories about collective archetypes. In 1941 he acquired

some exceptional books. This included There is No Natural

Religion (1794) [fig. 1], an “illuminated” book of eleven

color-printed relief etchings with pithy text critiquing the

reductive philosophical materialism of his day; a set of the

engraved Illustrations to the Book of Job (1825) in its

original binding; and a copy of Blake’s engravings illustrating

Edward Young’s Night Thoughts (1797) , one of two copies

believed to have been hand-colored by Blake himself.

...

At the same time that the Mellons were immersed in the worlds of

Jung and Blake, Mary began to form a major collection of

alchemical books and manuscripts inspired by Jung’s own collection

of similar material. But the return to civilian life was soon

clouded by tragedy. In October 1946 after Paul had been home only

a year, Mary Mellon died suddenly from an asthma attack.

...

In the early 1950s Paul Mellon drifted away from Jungian

influence and began almost a decade of Freudian analysis in

Washington DC, a time he also got to know Anna Freud in London

before becoming a significant supporter of her Foundation and what

became the Anna Freud Centre for the psychiatric treatment of

children. It was in 1953, as he was exploring Freudian psychology,

that Paul Mellon bought his most important Blake book, Jerusalem

The Emanation of the Giant Albion, a book that is at once

Blake’s most difficult but also his greatest.

|

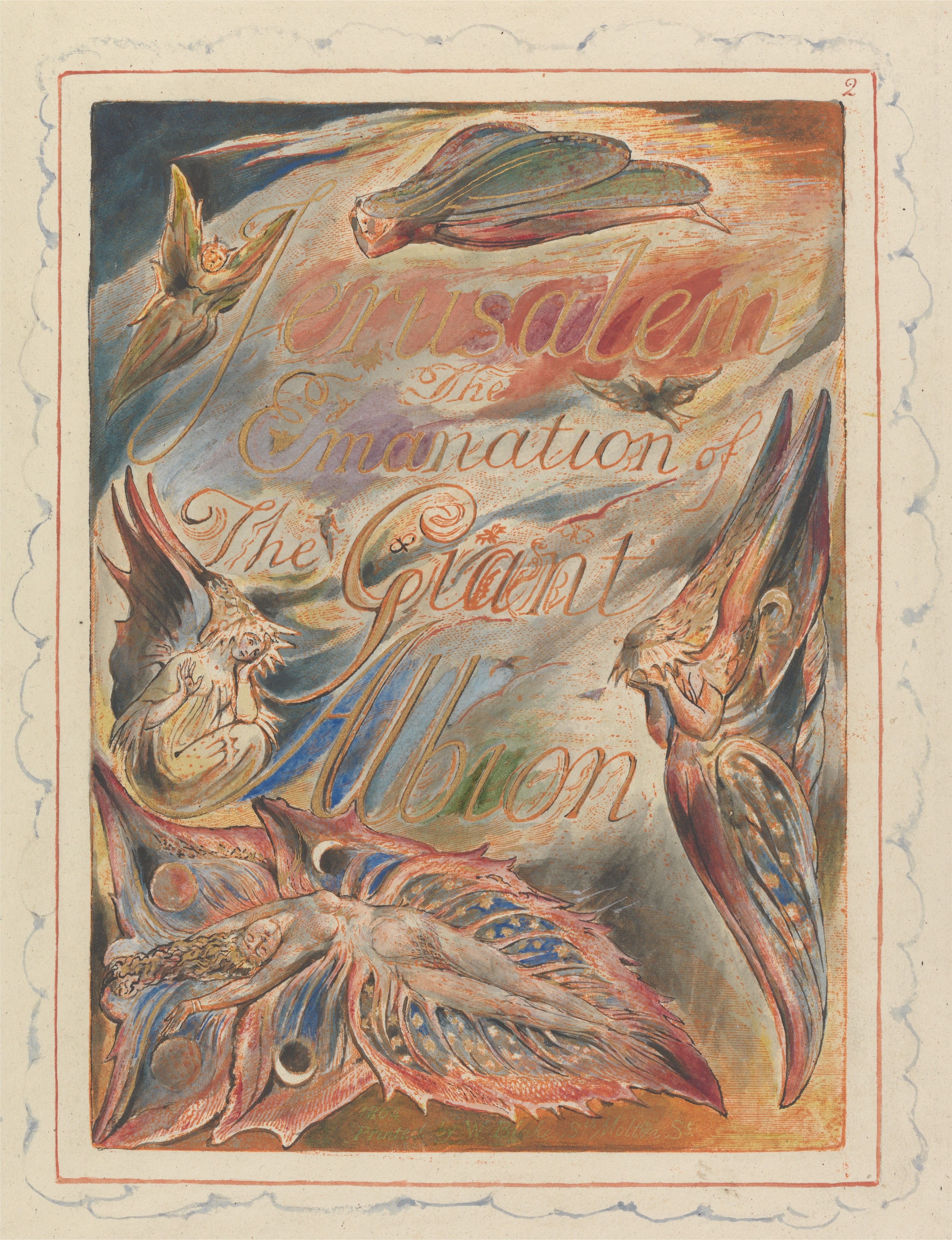

| Yale Center for British Art Jerusalem, The Emanation of the Giant Albion Title Page, Copy E |

For Blake, Imagination was the world of real essences of which the visible world was merely a faint echo. He once argued that “This World of Imagination is the World of Eternity. . . . This World is Infinite & Eternal whereas the world of Generation or Vegetation is Finite & Temporal.” Paul Mellon’s interest in psychology is one reason why Blake held such a lifelong fascination given that Blake’s own life’s work was to free the Imaginative faculty from the forces of repression. Despite the incomprehension of his contemporaries and his poverty, Blake kept his devotion to spiritual and mental freedom alive until the day he died. This impulse has remained a vital force long after his death. And in his final months he explained to George Cumberland that his physical body might be 'feeble & tottering, but not in Spirit & Life, not in the Real Man The Imagination which Liveth for Ever.'"

The extent of the Blake works in the Yale Center for British Art is revealed at this site.

No comments:

Post a Comment