Crabb Robinson, Blake, and Perthes's Vaterländisches Museum (1810–1811)

"Crabb Robinson's essay on Blake was published anonymously in the single issue of the second volume of the Vaterländisches Museum, immediately after the review of Bouterwek's work, thus representing a bibliographic and symbolic extension of the latter's history of European literature. Crabb Robinson's was the last item to be published before the magazine's demise, and the third to be devoted to a visual artist – the other two being Raphael and Goethe's friend, Wilhelm Tischbein (Vaterländisches Museum 1810, 120–23 and 230–42 respectively). Crabb Robinson's piece was not the first account of Blake in Germany. By 1789 the artist was known well enough to be listed in Carl Heinrich von Heinecken's Dictionnaire des artistes (1778–1790), published in Leipzig (Heinecken iii, 3). Blake's 1797 engravings for Edward Young's Night Thoughts (1742–1745), which had been circulating in Germany since approximately 1800, had also been commented upon by the novelist Jean Paul Richter in several of his letters.9 Richter had received a copy of Young's Night Thoughts from Emil Leopold August, Duke of Sachsen-Gotha-Altenburg, though he feigned to ignore the identity of his benefactor (Bentley, Blake Records 113–15).Crabb Robinson started to think more carefully about his piece on Blake when Perthes, whom he had met during his second stay in Hamburg between January and September 1807, asked him to “send him an article for a new German magazine entitled Vaterländische Annalen” (Bentley, Blake Records 296). Crabb Robinson had just seen Blake's works at an exhibition at 28 Broad Street, in London's Golden Square, and had been fascinated by the talents of this “insane poet painter & engraver” (Bentley, Blake Records 296). Years later, in his Reminiscences, Crabb Robinson also confessed that he had been “deeply interested by the Catalogues as well as the pictures” of Blake, and that he therefore “took four copies” (Bentley, Blake Records 298–99). It is this catalogue that provided the main inspiration for his essay in the Vaterländisches Museum, though Crabb Robinson also gleaned some biographical details from Benjamin Heath Malkin's own account of the artist in A Father's Memoirs of his Child (1806) and from Henry Fuseli's introduction to the 1808 edition of Blair's Grave. The essay was originally written in English and was subsequently translated into German by a certain Dr Julius, a doctor and friend of Perthes with whom he co-edited the Vaterländisches Museum (Wright 138–39).

Crabb Robinson acknowledged that the primary goal of his essay was to make Blake “as well known as possible,” though he did confess that he knew “too little of his history to claim to give a complete account of his life” (Bentley, Blake Records 601 and 594). Crabb Robinson's modest rhetorical style further surfaces in the assertion that his piece had “nothing in it of the least value” (Bentley, Blake Records 594). Crabb Robinson's self-effacing conviction may have partly stemmed from the fact that his observations were based entirely on Blake's texts and pictures; they did not include any personal details on the artist, whom the writer had not yet met in person. Introduced by an epigraph from Shakespeare's Midsummer Night's Dream – “The lunatic, the lover, and the poet / Are of imagination all compact,” – Crabb Robinson's essay quickly moves on to some fleeting observations about the complex yet “attractive” (Bentley, Blake Records 594) union of genius and madness. Crabb Robinson manifestly saw Blake as an unusual artist and individual, describing him as the most prominent and representative member in the whole race of “ecstatics, mystics, seers of visions, and dreamers of dreams” (Bentley, Blake Records 594). Throughout the essay, Crabb Robinson underlines Blake's eccentric singularity and his stubbornness in following his own artistic path. He believes that the painter's emerging genius is distinguished by its lack of interest and concern for the “usual, ordinary employment” (Bentley, Blake Records 595) of his friends and fellow artists. Although Crabb Robinson views Blake's artistic deviance and his obstinate wish for aesthetic independence as a sign of strength and superior talent, he also believes that the artist's insistence on self-reliance was a decisive element in keeping him confined to relative obscurity, especially at the beginning of his career.

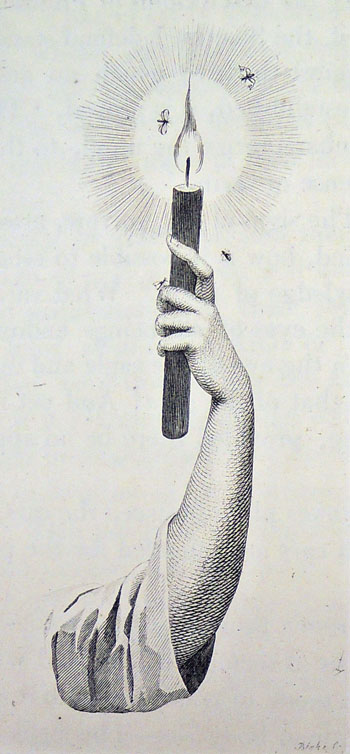

Throughout, Crabb Robinson's essay combines aesthetic judgement and factual information; it includes details about Blake's birth in London, his apprenticeship with the engraver James Basire, his passion for Gothic architecture, his drawing excursions to Westminster Abbey, and his activity as a collector of engravings (Bentley, Blake Records 594). The main bulk of his piece, however, focuses on describing the technique and the meaning of Blake's art and poetry. Several paragraphs are devoted to Blake's linear designs: “His greatest enjoyment,” Crabb Robinson writes, “consists in giving bodily form to spiritual essence” (Bentley, Blake Records 597). Crabb Robinson interprets Blake's intercourse with the spiritual world as congruent with that of Emanuel Swedenborg, whom Crabb Robinson sees as a direct source of inspiration for the artist. The author's commentaries on Blake's pictures and linear style are articulated in the idiom of a connoisseur. His disapproval of Blake's sweeping condemnation of the Dutch and Venetian masters – whom the artist qualifies as “most cruel . . . and most outrageous demons” (Bentley, Blake Records 596) – also testifies to Crabb Robinson's knowledge of the visual arts and his understanding of contemporary aesthetic currents.

The remarks Crabb Robinson makes about Blake's poetic activities are less powerful. Although he admits that Blake's “poems breathe the same spirit and are distinguished by the same peculiarities as his drawings and his critical prose” (Bentley, Blake Records 600), he believes that the metre of the poems included in the Poetical Sketches “is usually [so] loose and careless as to betray a total ignorance of the art.” Nonetheless, Crabb Robinson admits that “there is a wildness and loftiness of imagination in certain dramatic fragments which testifies to genuine poetical feeling” (Bentley, Blake Records 600–1). Several poems are inserted in the essay, in the original and in translation, including “To the Muses,” the “Introduction” from the Songs of Innocence, “Holy Thursday,” “The Tyger,” and “The Garden of Love.” Crabb Robinson's critical appreciation of these texts usually consists of brief, undeveloped commentaries: whilst he believes that Blake's Songs of Innocence are “child-like songs of the greatest beauty and simplicity,” he remains puzzled as to the significance of Songs of Experience, which he reads as “metaphysical riddles and mystical allegories” (Bentley, Blake Records 601).10 Crabb Robinson also confesses his inability to give a sufficient account of several poems, including Europe, Prophecy, and America, which he finds are too “obscure . . . mysterious and incomprehensible” (Bentley, Blake Records 602).

Significantly, Crabb Robinson concludes his essay by emphasizing the German character of Blake's art and poetry and the appropriateness of his subject for a German periodical. Crabb Robinson clearly counted upon a more widespread appreciation in Germany for the mystery and obscurity surrounding Blake's personality and work – an obscurity, he adds in his essay, “which one would expect from a German rather than an Englishman,” and which “assuredly cannot lessen the interest which all men, Germans in a higher degree even than Englishmen, must take in the contemplation of such a character” (Bentley, Blake Records 603). Crabb Robinson's evaluation was the first of a long series of other statements that have acknowledged the proximity between Blake's aesthetics and those of the German Frühromantik.11 Blake's affinities with his German contemporaries were certainly no coincidence. If such affinities might be attributed to parallel developments from similar literary, visual, and philosophical sources, including Jacob Boehme, they were also the result of several direct encounters with Henry Fuseli and Johann Jacob Lavater, whose frontispiece to the Aphorisms on Man (1789) Blake engraved.12 In Lavater's work, in particular, Blake had found support for his more transcendental and idealistic tendencies, and his belief that external, physionomical appearances reflect internal realities (Earle).

...If we bear in mind the cultural and political context in which Perthes's magazine was published, the decision to include Crabb Robinson's piece on Blake in the Vaterländisches Museum may appear less surprising than at first sight. The text, with its implicit and explicit references to the Germanic character of Blake's art and poetry, underpinned Perthes's aim to promote Germanic art, literature, and culture, indeed to keep alive and strengthen the Germanic spirit among his readers. Besides Blake's aesthetic affinities with Runge, and Crabb Robinson's overt admission of the Germanic-ness of his subject at the end of his essay, other, perhaps more oblique, references in his article underline the close connections between England and Germany. Having acknowledged that among Blake's “aberrations,” there were also “gleams of reason” (Bentley, Blake Records 598), Crabb Robinson writes that “The Protestant author of Herzensergiessungen eines kunstliebenden Klosterbruders created the character of a Catholic in whom religion and love of art are mixed into one essence, and this same person, remarkably enough, has turned up in Protestant England” (Bentley, Blake Records 599). Crabb Robinson's allusion to Wilhelm Heinrich Wackenroder's influential book (first published anonymously in Berlin in 1797) is particularly significant for several reasons. Not only does it identify Blake as the English re-incarnation of a fictive German artist who succeeded in producing an art that was the product of both emotional feelings and religious devotion – a characteristic, as we have seen, essential for Pietists like Runge and Perthes:21 significantly, Crabb Robinson's reference to Wackenroder's Herzensergiessungen is also an allusive reference to medieval art and literature, and especially to the “sacred” Albrecht Dürer. In truth, Wackenroder's assessment of Dürer was instrumental in changing certain views that eighteenth-century critics had articulated about the artist, including his provincialism and his desire to remain in Germany (Sanford 446). Rather than interpreting Dürer's localism as a lack of artistic ambition, Wackenroder presented Dürer's provincialism as a laudable mark of national pride.

In his biographical essay, Crabb Robinson specifically singles out Dürer as one of Blake's idols.22 The implicit and explicit presence of Dürer in Crabb Robinson's piece was thus highly symbolic: on the one hand, it underpinned the patriotic message of Perthes's magazine (Dürer, we remember, acquired his iconic status during the rise of German nationalism); on the other hand, however, by its transfer of the protagonist of the Herzensergiessungen from Germany to England, it simultaneously undermined and neutralized the more nationalistic element latent in the Herzensergiessungen and relocated Dürer within a more international and cosmopolitan environment.

...

ConclusionClearly, Perthes's Vaterländisches Museum negotiated the binary and antagonistic impulses between nationalism and cosmopolitanism, between the local and the general, between the German and the Germanic. Although Perthes's periodical served political and nationalistic ends in its effort to infuse a sense of power and self-confidence into its readers and stir them into action, the Vaterländisches Museum still in some measure espoused the cosmopolitan outlook of the time, putting forward the idea that all human beings belong to the human community.

Within such a political and cultural framework, Crabb Robinson's piece on Blake articulated the very tension with which Perthes was dealing. Implicitly as well as explicitly, Blake emerged as a figure that channelled Perthes's conflicting loyalties. Interestingly, the format of the periodical itself and the position of Crabb Robinson's essay, sandwiched as it was between the review of Bouterwek's Von der neuesten englischen Poesie and the Schluss-Anmerkung, moulded Blake's reputation in two reconcilable ways: not only did it present him as a figure whose art contained and could transmit elements of German culture and German identity, but at the same time it also introduced the English poet as a quintessentially cosmopolitan artist, a man speaking a language that went beyond borders and beyond nationalities.

The initial success of Perthes's periodical exceeded all expectations. It was, however, short-lived. Only one year after its first issue, in 1811, the Vaterländisches Museum ceased publication. The purpose and ideals at the core of Perthes' project were suddenly dashed by Napoleon's annexation of Hamburg to the French Empire in 1811. Indeed, Perthes argued that because he no longer had a “Vaterland,” there could be no Vaterländisches Museum anymore. Deeply affected by the turn of political events, and increasingly aware of the dangers of pursuing his publishing activities, Perthes brought the publication of his journal to an end."

Marriage of Heaven and Hell, Plate 27, (E 44)

A Song of Liberty

15. Down rushd beating his wings in vain the jealous king: his

grey brow'd councellors, thunderous warriors, curl'd veterans,

among helms, and shields, and chariots horses, elephants:

banners, castles, slings and rocks,

16. Falling, rushing, ruining! buried in the ruins, on Urthona's

dens.

17. All night beneath the ruins, then their sullen flames faded

emerge round the gloomy king,

18. With thunder and fire: leading his starry hosts thro' the

waste wilderness he promulgates his ten commands,

glancing his beamy eyelids over the deep in dark dismay,

19. Where the son of fire in his eastern cloud, while the

morning plumes her golden breast,

20. Spurning the clouds written with curses, stamps the stony

law to dust, loosing the eternal horses from the dens of night,

crying

Empire is no more! and now the lion & wolf shall cease.

Chorus

Let the Priests of the Raven of dawn, no longer in deadly

black, with hoarse note curse the sons of joy. Nor his accepted

brethren whom, tyrant, he calls free; lay the bound or build the

roof. Nor pale religious letchery call that virginity, that

wishes but acts not!

For every thing that lives is Holy"

No comments:

Post a Comment