First Posted Match 2019

|

Wikipedia Commons

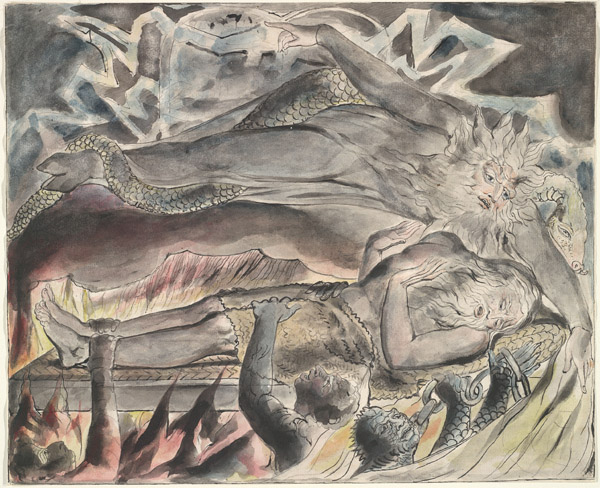

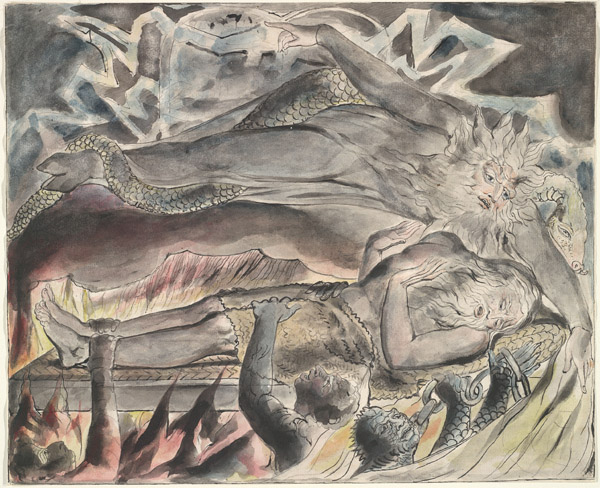

Illustration to the Book of Job

Linnell Set |

This is an extract from Chapter Four (FAITH) of Ram Horn'd With Gold by Larry Clayton. In 'Milton' Blake speaks of two streams flowing from a fountain in a rock of crystal: one goes straight to Eden; the other is more torturous. They represent of course two possible journeys through life, and he could speak of both because he lived both. The first stream represents the child-like consciousness that enabled Blake (that enables anyone gifted with it) to live every moment in the light of Eternity. The other, more common path wanders all over this God-forsaken vale of tears, but it winds up at the same place.

That's the most incredible good news for anybody who can hear it. The apostle Paul hinted at it a time or two; perhaps it was the truth that he was forbidden to tell. Origen believed it, no doubt one of the reasons the Church Fathers kicked him out. In the 19th Century an entire denomination arose whose primary emphasis was this particular good news--the Universalists. Actually this good news could not be pronounced with authority except by someone like Blake who had traveled both journeys; he knew whereof he spoke.

If you believe that all came originally from the One and that in the fullness of time all things in Christ are gathered together in one, then as a consequence the two paths do meet at the end as Blake claimed. We can put this in a more properly theological context with Blake's expressed response to the Calvinistic doctrine of Double Predestination.

Double Predestination contains as its lower half the grim old notion of Hell that has probably done as much as anything else in theology to discredit the Christian faith in the eyes of the modern world. Calvin taught the hoary old superstition that most of the world's population are destined to live without Christ and to die and move on to eternal torment; a lucky few have a happier destiny. The lucky few included Calvin of course and his friends, especially his obedient friends. In contrast Origen, perhaps Paul, and surely Blake believed in single predestination: the two streams converge at the end.

Blake expended an enormous amount of his creative energy combating Double Predestination. He heaped scorn upon scorn on the Calvinistic God who curses his children. His break with Swedenborg followed his discovery that Swedenborg was a "Spiritual Predestinarian, more abominable than Calvin's". He later lamented over him and called him the "Samson, shorn by the Churches."

In Milton Blake ironically inverted the Calvinistic categories of 'elect' and 'reprobate'. With incredible elegance he used Jesus' words on Calvin like a two edged sword. He simply pronounced on behalf of Christ the obvious truth, as if to say, "Calvin, your doctrine is of the world, and your first shall be last in my kingdom."

Double Predestination is a consequence of a more fundamental error of Rahab, the whore of Babylon, the organized Church, "Imputing sin and righteousness to individuals". Blake addressed that error with his doctrine of states, which we look at in a moment.

In Marriage of Heaven and Hell Blake examined most directly the conventional idea of Hell and pronounced it a delusion of a certain type of mind. In Visions of the Last Judgment he gave his straightforward views about the meaning of the biblical Hell. Again in 'Jerusalem', "What are the Pains of Hell but Ignorance, Bodily Lust, Idleness & devastation of the things of the Spirit?"

However the conventional Hell does seem to have some biblical basis: Isaiah 66:24, Mark 9:43ff, Matthew 25:41 provide examples. How do you deal with all those scriptures? In the first place Blake felt perfectly free to discount anything in the Bible that he found incongruent with his vision, at least to discount its conventional meaning. The immediate experience always exercised authority over anything second hand. The inerrancy of scripture, another of the Five Fundamentals, meant just about as much to him as Double Predestination.

In the second place, although the doctrine of hell has most often been used as a means of anathematizing those with whom one disagrees, there are certainly more creative ways to deal with it. Blake chose one of these, what he called the doctrine of states. In a conversation with the "seven Angels of the Presence" Milton is told by Lucifer: "We are not individuals but states.../ Distinguish therefore states from individuals in those states."

And at the end of the first chapter of Jerusalem the daughters of Beulah pray as follows:"Descend O Lamb of God & take away the imputation of Sin

By the Creation of States & the deliverance of Individuals Evermore Amen...

But many doubted & despaird & imputed Sin & Righteousness

To Individuals & not to States, and these Slept in Ulro"

(Jerusalem, 25.12 Erdman 170)

To distinguish states from individuals is the only means of forgiveness of sins. In the centuries since Blake enlightened Christians have learned to condemn sin without condemning the sinner. The most enlightened condemn no one, realizing that they themselves are as sinful as anyone else. For such a consciousness the only authentic preaching becomes confessional preaching.

The relationship between Blake's doctrine of states and the conventional doctrine of hell becomes clear in Plate 16 of the Job series where Job and his wife watch the 'old man' in themselves take the plunge with their master "into the everlasting fire prepared for the devil and his angels". This of course is a spiritual or psychic event. The crude and ludicrous superstition of the conventional doctrine of hell stems from a spiritual blindness that attempts to impose the material upon the Beyond--once again the Lockian fallacy, the assumption that 'material' is 'real'.

The Last Judgment in Blake is the consummation devoutly to be hoped for when truth takes its rightful place in man's psyche. Error is "burnt up the Moment Men cease to behold it". The person wedded to error finds this a fearsome prospect; the one who wants to be free finds it a glorious one. We're all headed for the last judgment--by the direct childlike route or the torturous worldly route. It's the fervent hope of the eternalist and the bane of the materialist. Blake as was said before, traveled both routes. His exquisite lyrics attest to the first; his (often tormented) prophetic declamation to the second. The childlike route is so crystal clear as to need little explanation; the second obviously needs a great deal. Looking closely at the first may be good preparation for the second.

An incident from Blake's last years suggests something of the nature of the torturous route which was Blake's life. The old poet was telling the story of the Prodigal Son. He got to the moment when the wandering boy at last returns to the Father. At that point Blake broke down in tears; he couldn't go on. The story casts a revealing light on a primitive relationship that must have provided a lot of the dynamic for Blake's creativity.

Psychologists tell us that a person's early relationship with his father has a great bearing on his image of God. Applying that idea to Blake's poetry one could infer that Blake as a child had a gruesome relationship with his father. However we find little suggestion of this in the biography. On the contrary the preponderance of the evidence suggests a permissive and understanding parent. (The only exception seems to be the threat to beat the eight year old for his 'lie' about the tree full of angels.) In any event 'father' has unpleasant associations in Blake's poetry, especially in the theological realm. He adored Jesus, but he obviously had trouble believing Jesus' word about the loving Father.

The Neo-platonic interpreters have theorized that Blake couldn't forgive the Creator for condemning us to this prison house of mortal life. I think a more universal explanation fits the facts. Everyone has difficulty forgiving his father and/or creator for the dimensions of horror in life which threaten in one way or another to overwhelm the psyche. Few or none of us have done a really adequate job of this. Most often we've repressed the sensitive idealist; we've closed off from consciousness those unpleasant ultimate realities which seem to have no answer.

"Did he who made the Lamb make thee?" Has anyone really asked that question since 1794? Nietzsche asked it and went crazy. In our generation Jung has come closest, and that's what makes him great. Most of us, even the best of Christians, have partitioned off and closed out that ultimate question, the ultimate doubt expressed by the dying Saviour on the cross. This William Blake could not do; like Jesus he was condemned to face consciously the penalty of our finitude.

Songs of Innocence and Experience, Song 42, Erdman 24

"The Tyger.

Tyger Tyger, burning bright,

In the forests of the night;

What immortal hand or eye,

Could frame thy fearful symmetry?

In what distant deeps or skies.

Burnt the fire of thine eyes?

On what wings dare he aspire?

What the hand, dare sieze the fire?

And what shoulder, & what art,

Could twist the sinews of thy heart?

And when thy heart began to beat,

What dread hand? & what dread feet?

What the hammer? what the chain,

In what furnace was thy brain?

What the anvil? what dread grasp,

Dare its deadly terrors clasp!

When the stars threw down their spears

And water'd heaven with their tears:

Did he smile his work to see?

Did he who made the Lamb make thee?

Tyger Tyger burning bright,

In the forests of the night:

What immortal hand or eye,

Dare frame thy fearful symmetry?"

Frye has spoken of the 'abyss of consciousness'. Enion, the primeval mother in 4Z is condemned to it by her love of her children. At the end of Night ii she calls our attention to this blindness which we have chosen and its opposite, the abyss of consciousness which she (and Blake in her) is condemned to face; here is her complaint.

Something is terribly wrong in this created universe, and in the face of this underlying wrongness the idea of a loving Father as Creator simply doesn't fit all the facts. This consciousness, which Blake shared with Dostoevsky in the person of Ivan Karamazov, interrupted Blake's childlike innocence and precipitated the torturous journey "through the Aerial Void and all the Churches".

Probably a majority of people will always refuse such an invitation; they will cling to the refuge of their Church, or Bible, or President, or fraternity, or whatever form of authority they have made their obeisance to, whatever they have found to block out the abyss of consciousness. A few will have at least a sympathetic or vicarious interest in the problem posed by Blake and Dostoevsky. A handful will perceive that to realize their full humanity and the God Within they must proceed beyond innocence. They, too, must take that long journey and plumb life to its wholeness. The art of Blake offers a good map for the trip.

_object_45_The_Little_Vagabond.jpg)