|

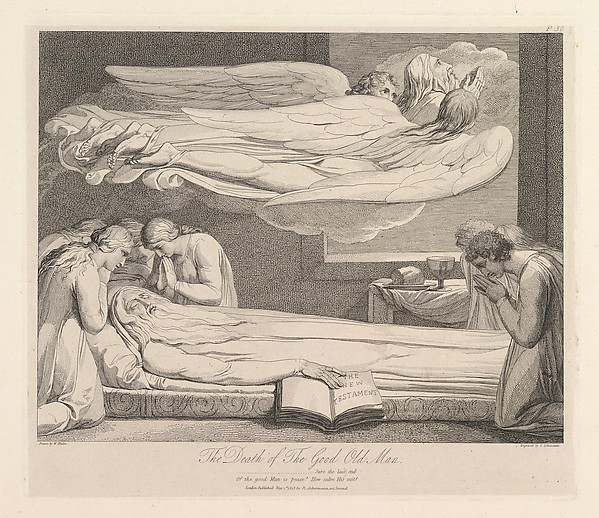

| Metropolitan Museum The Death of the Good Old Man from The Grave, a Poem by Robert Blair |

When Blake created his image of the Resurrection of Christ he had

to have been recalling his own experience of the ascent of his brother

Robert's spirit as it left his body when he died. Blake was

attuned to the spiritual world whose outlines were not obscured to

his spiritual eye. The image of his beloved brother leaving his

body and beginning his journey to the Father would have been

indelibly imprinted on William's imagination. Having seen his brother's ascent he could picture

the ascent of Jesus in a most

convincing and inspiring way.

Peter Ackroyd comments in Blake: A Biography on Blake's

continued ability to see visions into his adulthood:

"When Blake created his image of the Resurrection of Christ he had

to have been recalling his own experience of the ascent of his brother

Robert's spirit as it left his body when he died. Blake was

attuned to the spiritual world whose outlines were not obscured to

his spiritual eye. The image of his beloved brother leaving his

body and beginning his journey to the Father would have been

indelibly imprinted on William's

"One early biographer has explained how 'the Scripture overawed

his imagination' - to such an extent that he saw it materialising

around him. It is not an uncommon gift and one friend, George

Richmond, commented in the margin of Gilchrist's Life, 'He

said to me that all children saw "Visions" and that the substance

of what he added is that all men might see them but for

worldliness or unbelief, which blinds the spiritual eye.' " (Page

35)

Blake's first biographer Alexander Gilchrist

in The Life of William Blake (1863), writes of the

relationship of William and Robert Blake until they were

physically but not spiritually parted by Robert's death:

"With Blake and with his wife, at the print shop in Broad Street,

Robert for two happy years and a half lived in seldom disturbed

accord. Such domestications, however,

always bring their own trials, their own demands for mutual

self-sacrifice. Of which the following anecdote will supply a

hint, as well as testify to much amiable magnanimity on the part

of both the younger members of the household. One day, a dispute

arose between Robert and Mrs. Blake. She, in the heat of

discussion, used words to him, his brother (though a husband

too) thought unwarrantable. A silent witness thus far, he could

now bear it no longer, but with characteristic impetuosity— when

stirred—rose and said to her: "Kneel down and beg Robert's

pardon directly, or you never see my face again!" A heavy

threat, uttered in tones which, from Blake, unmistakably showed

it was meant. She,

poor thing! "thought it very hard," as she would afterwards

tell, to beg her brother-in-law's pardon when she was not in

fault! But being a duteous, devoted wife, though by nature

nowise tame or dull of spirit, she did kneel down and meekly

murmur, "Robert, I beg your pardon, I am in the wrong." "Young woman, you lie !"

abruptly retorted he : "/ am in the wrong!"

No wonder he could paint such scenes! With him they were work'y-day experiences." (Page 60)

Letters, to Hayley, May 6 1800, (E 705)

"I know that our

deceased friends are more really with us than when they were

apparent to our mortal part. Thirteen years ago. I lost a

brother & with his spirit I converse daily & hourly in the

Spirit. & See him in my remembrance in the regions of my

Imagination. I hear his advice & even now write from his

Dictate--Forgive me for expressing to you my Enthusiasm which I

wish all to partake of Since it is to me a Source of Immortal

Joy even in this world by it I am the companion of Angels. May

you continue to be so more & more & to be more & more perswaded.

that every Mortal loss is an Immortal Gain. The Ruins of Time

builds Mansions in Eternity"

No comments:

Post a Comment