This post was first published in August 2013 in celebration of the 50th Anniversary of the March on Washington. It is republished today in honor of Martin Luther King's 86TH birthday.

There follows a quote from Martin Luther King's letter written from the

jail in Birmingham, Alabama in April of 1963. King had been

jailed for refusing to discontinue his protests against the abuse of

justice in the segregated South. He took the opportunity of his

imprisonment to make a statement of the foundations of the movement to

non-violently enact 'extreme' measures to replace the passive acceptance

of conditions which were an outrage to the conscience of just men.

"I

am cognizant of the interrelatedness of all communities

and states. I

cannot sit idly

by in Atlanta and not be concerned about what happens in Birmingham.

Injustice anywhere is

a threat

to justice everywhere. We are caught in an inescapable network

of mutuality, tied in a

single garment

of destiny. Whatever affects one directly, affects all indirectly.

Never again can we

afford to live with

the narrow, provincial "outside agitator" idea. Anyone who lives

inside the United States

can never be

considered an outsider anywhere within its bounds.

...

Oppressed people cannot remain oppressed forever. The yearning for freedom eventually manifests itself, and that is what has happened to the American Negro. Something within has reminded him of his birthright of freedom, and something without has reminded him that it can be gained. Consciously or unconsciously, he has been caught up by the Zeitgeist, and with his black brothers of Africa and his brown and yellow brothers of Asia, South America and the Caribbean, the United States Negro is moving with a sense of great urgency toward the promised land of racial justice. If one recognizes this vital urge that has engulfed the Negro community, one should readily understand why public demonstrations are taking place. The Negro has many pent up resentments and latent frustrations, and he must release them. So let him march; let him make prayer pilgrimages to the city hall; let him go on freedom rides -and try to understand why he must do so. If his repressed emotions are not released in nonviolent ways, they will seek expression through violence; this is not a threat but a fact of history. So I have not said to my people: "Get rid of your discontent." Rather, I have tried to say that this normal and healthy discontent can be channeled into the creative outlet of nonviolent direct action. And now this approach is being termed extremist. But though I was initially disappointed at being categorized as an extremist, as I continued to think about the matter I gradually gained a measure of satisfaction from the label. Was not Jesus an extremist for love: "Love your enemies, bless them that curse you, do good to them that hate you, and pray for them which despitefully use you, and persecute you." Was not Amos an extremist for justice: "Let justice roll down like waters and righteousness like an ever flowing stream." Was not Paul an extremist for the Christian gospel: "I bear in my body the marks of the Lord Jesus." Was not Martin Luther an extremist: "Here I stand; I cannot do otherwise, so help me God." And John Bunyan: "I will stay in jail to the end of my days before I make a butchery of my conscience." And Abraham Lincoln: "This nation cannot survive half slave and half free." And Thomas Jefferson: "We hold these truths to be self evident, that all men are created equal . . ." So the question is not whether we will be extremists, but what kind of extremists we will be. Will we be extremists for hate or for love? Will we be extremists for the preservation of injustice or for the extension of justice? In that dramatic scene on Calvary's hill three men were crucified. We must never forget that all three were crucified for the same crime--the crime of extremism. Two were extremists for immorality, and thus fell below their environment. The other, Jesus Christ, was an extremist for love, truth and goodness, and thereby rose above his environment. Perhaps the South, the nation and the world are in dire need of creative extremists."

...

Oppressed people cannot remain oppressed forever. The yearning for freedom eventually manifests itself, and that is what has happened to the American Negro. Something within has reminded him of his birthright of freedom, and something without has reminded him that it can be gained. Consciously or unconsciously, he has been caught up by the Zeitgeist, and with his black brothers of Africa and his brown and yellow brothers of Asia, South America and the Caribbean, the United States Negro is moving with a sense of great urgency toward the promised land of racial justice. If one recognizes this vital urge that has engulfed the Negro community, one should readily understand why public demonstrations are taking place. The Negro has many pent up resentments and latent frustrations, and he must release them. So let him march; let him make prayer pilgrimages to the city hall; let him go on freedom rides -and try to understand why he must do so. If his repressed emotions are not released in nonviolent ways, they will seek expression through violence; this is not a threat but a fact of history. So I have not said to my people: "Get rid of your discontent." Rather, I have tried to say that this normal and healthy discontent can be channeled into the creative outlet of nonviolent direct action. And now this approach is being termed extremist. But though I was initially disappointed at being categorized as an extremist, as I continued to think about the matter I gradually gained a measure of satisfaction from the label. Was not Jesus an extremist for love: "Love your enemies, bless them that curse you, do good to them that hate you, and pray for them which despitefully use you, and persecute you." Was not Amos an extremist for justice: "Let justice roll down like waters and righteousness like an ever flowing stream." Was not Paul an extremist for the Christian gospel: "I bear in my body the marks of the Lord Jesus." Was not Martin Luther an extremist: "Here I stand; I cannot do otherwise, so help me God." And John Bunyan: "I will stay in jail to the end of my days before I make a butchery of my conscience." And Abraham Lincoln: "This nation cannot survive half slave and half free." And Thomas Jefferson: "We hold these truths to be self evident, that all men are created equal . . ." So the question is not whether we will be extremists, but what kind of extremists we will be. Will we be extremists for hate or for love? Will we be extremists for the preservation of injustice or for the extension of justice? In that dramatic scene on Calvary's hill three men were crucified. We must never forget that all three were crucified for the same crime--the crime of extremism. Two were extremists for immorality, and thus fell below their environment. The other, Jesus Christ, was an extremist for love, truth and goodness, and thereby rose above his environment. Perhaps the South, the nation and the world are in dire need of creative extremists."

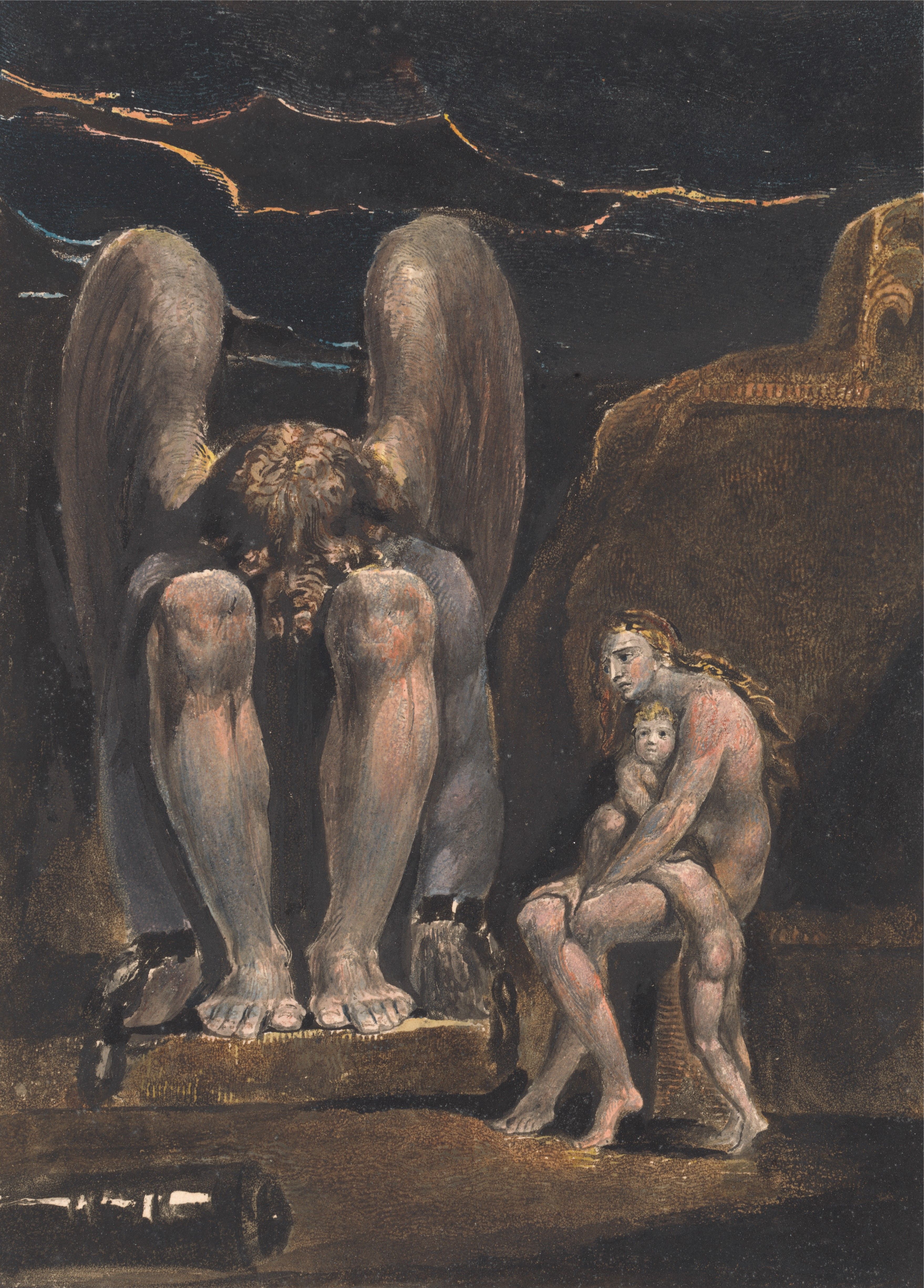

William Blake could be added to the list of men who were willing to

advocate extreme measures to effect the changes which would reverse

oppression. He spoke through his poetry especially through the prophetic

voice of Los and in the following poem.

|

Yale Center for British Art America, A Prophecy Frontispiece

|

Songs and Ballads, (E 489)

The Grey Monk

"I die I die the Mother said

My Children die for lack of Bread

What more has the merciless Tyrant said

The Monk sat down on the Stony Bed

The blood red ran from the Grey Monks side

His hands & feet were wounded wide

His Body bent his arms & knees

Like to the roots of ancient trees

His eye was dry no tear could flow

A hollow groan first spoke his woe

He trembled & shudderd upon the Bed

At length with a feeble cry he said

When God commanded this hand to write

In the studious hours of deep midnight

He told me the writing I wrote should prove

The Bane of all that on Earth I lovd

My Brother starvd between two Walls

His Childrens Cry my Soul appalls

I mockd at the wrack & griding chain

My bent body mocks their torturing pain

Thy Father drew his sword in the North

With his thousands strong he marched forth

Thy Brother has armd himself in Steel

To avenge the wrongs thy Children feel

But vain the Sword & vain the Bow

They never can work Wars overthrow

The Hermits Prayer & the Widows tear

Alone can free the World from fear

For a Tear is an Intellectual Thing

And a Sigh is the Sword of an Angel King

And the bitter groan of the Martyrs woe

Is an Arrow from the Almighties Bow

The hand of Vengeance found the Bed

To which the Purple Tyrant fled

The iron hand crushd the Tyrants head

And became a Tyrant in his stead"

4 comments:

Thank you for this fine piece of rhetoric by King, better I think than “I have a Dream” at the Lincoln Memorial, and which matches up so well to the poem by Blake.

“For a tear is an intellectual thing” — what an extraordinary line, from the greatest orator in English verse.

As you doubtless know, there’s a debate afoot to change our National Anthem from God Save the Queen (or King) when used on other than specifically royal occasions. One of the strongest contenders is "And did those feet", to the tune by Parry. Here’s an audio piece from the BBC discussing the issue http://www.bbc.co.uk/programmes/b06vnbcy

The overtly Christian connotations of Blake's 'Jerusalem' make it an unlikely choice for Britain's national anthem. I have a suggestion.

Here is a quintessential British song which is spiritual without being religious. It was written in a period not of war but of dramatic revolutionary social change. The message is encouraging but honest. It uses poetic language speaking of 'hour of darkness,' and 'broken hearted people' to connect with the world in need. It is characteristically British in understating both the hardships endured and the solutions available, but the determination and confidence are apparent.

'Let It Be' by John Lennon

When I find myself in times of trouble

Mother Mary comes to me

Speaking words of wisdom, let it be

And in my hour of darkness

She is standing right in front of me

Speaking words of wisdom, let it be

Let it be, let it be, let it be, let it be

Whisper words of wisdom, let it be

And when the broken hearted people

Living in the world agree

There will be an answer, let it be

For though they may be parted there is

Still a chance that they will see

There will be an answer, let it be

Let it be, let it be, let it be, let it be

Yeah, there will be an answer, let it be

Let it be, let it be, let it be, let it be

Whisper words of wisdom, let it be

Let it be, let it be, let it be, let it be

Whisper words of wisdom, let it be

And when the night is cloudy

There is still a light that shines on me

Shine on until tomorrow, let it be

I wake up to the sound of music

Mother Mary comes to me

Speaking words of wisdom, let it be

Let it be, let it be, let it be, let it be

There will be an answer, let it be

Let it be, let it be, let it be, let it be

Whisper words of wisdom, let it be

_______________

An interesting suggestion, Ellie. As an Englishman (“Jerusalem” being a poem which mentions England rather than Britain) I see it as patriotic rather than Christian in the popular imagination within these shores. If “those feet”—Joseph of Arimathea and the young Jesus—did come here, it boosts a perception of our land as blessed, without imposing any religious allegiance or obligation to exclude anyone.

Its last two verses provide a rousing call to action, without being warlike & bloody like France’s Marseillaise. It’s grand and mysterious but non-specific.

Ideally a national anthem should bring people together, with words like “we shall” or “let us”. Blake undertakes the action with “me” and “I”, which is perfect when sung to a rousing tune, and collectively amounts to “we” and “us”. And then he puts “we” in his last two lines, setting out the vague goal of building “Jerusalem in England’s green and pleasant land”. Intuitively we all know that Jerusalem is a symbol for Heaven on earth, not a place where Jews and Muslims live uneasily together at best.

Is “Let it Be” quintessentially British? Only, I suggest, to those who live far away from Britain. Here it’s an elegiac pop song by Paul McCartney, whose message is overtly passive and pacifist: “in times of trouble ... let it be.” Hardly a patriotic song to give us a sense of coming together in patriotism and common purpose.

I too thought it was by John Lennon, on the analogy of “Give Peace a Chance”, until I checked. Of course we have peaceniks here too, but the national anthem is required when our Olympic team wins a medal, more often than in times of trouble and loss.

Oops, I accepted the first attribution to Lennon without checking further.

In spite of the beauty and significance of Blake's poem, it wouldn't be easy for non-Christians to accept the Holy Lamb of God, or the Divine Countenance being the means by which England achieved perfection. But you are right that it is a stirring experience to sing of receiving the instruments through which the ideal society might be built.

Not all Americans favor the Star Spangled Banner as our anthem but I do. It refers to a specific incident when our defenses held and symbol of our independence endured. Not everyone knows the coincidences which contributed to the writing of the song. The tale is of the building of the star-shaped fort, the sewing of the flag which could be seen from a great distance, and the imprisonment of the poet on a ship where he could witness from afar the battle taking place overnight. Many find the anthem difficult to sing, but the story behind the words makes singing it a rewarding experience. I especially enjoy singing it on the beach at sunrise.

Post a Comment