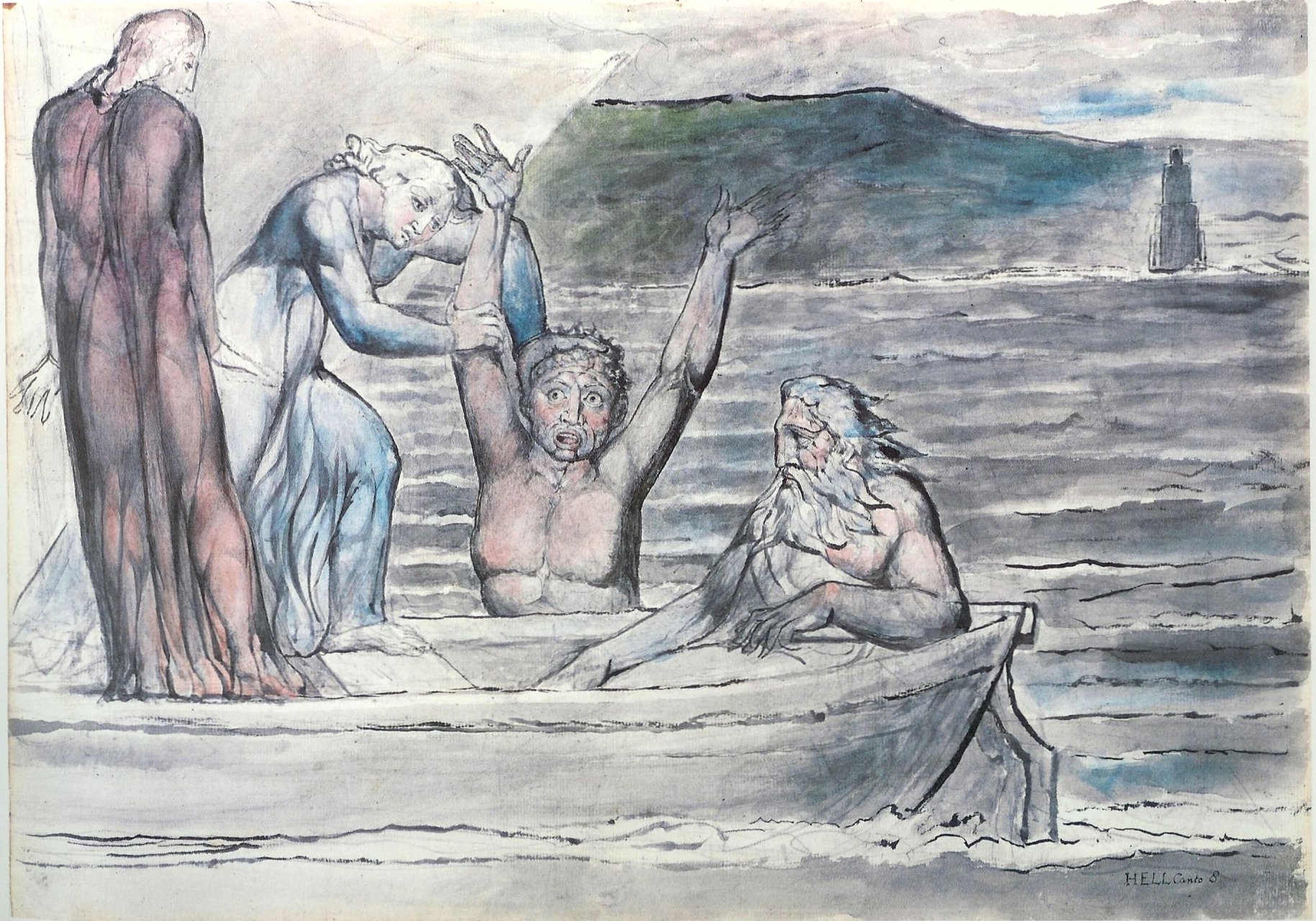

While we were running through the dead canal, Uprose in front of me one full of mire, And said, "Who 'rt thou that comest ere the hour?" And I to him: "Although I come, I stay not; But who art thou that hast become so squalid?" "Thou seest that I am one who weeps," he answered. And I to him: "With weeping and with wailing, Thou spirit maledict, do thou remain; For thee I know, though thou art all defiled." Then stretched he both his hands unto the boat; Whereat my wary Master thrust him back, Saying, "Away there with the other dogs!"

|

| Virgil repelling Fllippo Argenti from the Boat Plate 18 |

Filippo Argenti or Filippo Argente (13th century), a famous politician and a citizen of Florence, was a member of the Cavicciuoli branch of the aristocratic family of Adimari, according to Boccaccio.[1] Filippo's children were Giovanni Argente & Salvatore Argente. Salvatore travelled to Spain and first was established in Barcelona and his descendents in Valencia, where his grandson Salvatore was established in the small village of Navarres and the surname changed as Argente. The Adimari family were part of the Black Guelph political faction.

Filippo is reputed to have received the nickname "Argenti" by having his horse shod with silver. He makes an appearance in the Decamerone, 9.8, where Boccaccio tells a story that involves his temper.[1] The Firenze's storia talks about his silver hair. He was a very tall man, very burly, bizarre, famous for his iron fists.

Filippo Argenti appears as a character in the fifth circle of Hell in the Inferno, the first part of Dante's Divine Comedy. Filippo is among the wrathful in the river Styx, and accosts Dante as the latter crosses the Styx. Filippo is then torn into pieces by the other wrathful in the river Styx after this encounter with Dante and Virgil.

Early commentators recount various incidents to explain the antipathy between Dante and Filippo:

- Filippo once slapped Dante,

- Filippo's brother had taken Dante's possessions after Dante's exile from Florence,

- Filippo's family had opposed Dante's return from exile

From Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia:

The Divine Comedy (Italian: Divina Commedia) is an epic poem by Dante Alighieri, begun c. 1308 and completed 1320, a year before his death in 1321. It is widely considered the preeminent work of Italian literature[1] and is seen as one of the greatest works of world literature.[2] The poem's imaginative vision of the afterlife is representative of the medieval world-view as it had developed in the Western Church by the 14th century. It helped establish the Tuscan language, in which it is written, as the standardized Italian language.[3] It is divided into three parts: Inferno, Purgatorio, and Paradiso.

On the surface, the poem describes Dante's travels through Hell, Purgatory, and Paradise or Heaven;[4] but at a deeper level, it represents, allegorically, the soul's journey towards God.[5] At this deeper level, Dante draws on medieval Christian theology and philosophy, especially Thomistic philosophy and the Summa Theologica of Thomas Aquinas.[6] Consequently, the Divine Comedy has been called "the Summa in verse".[7]

The work was originally simply titled Comedìa and was later christened Divina by Giovanni Boccaccio. The first printed edition to add the word divina to the title was that of the Venetian humanist Lodovico Dolce,[8] published in 1555 by Gabriele Giolito de' Ferrari.

No comments:

Post a Comment