|

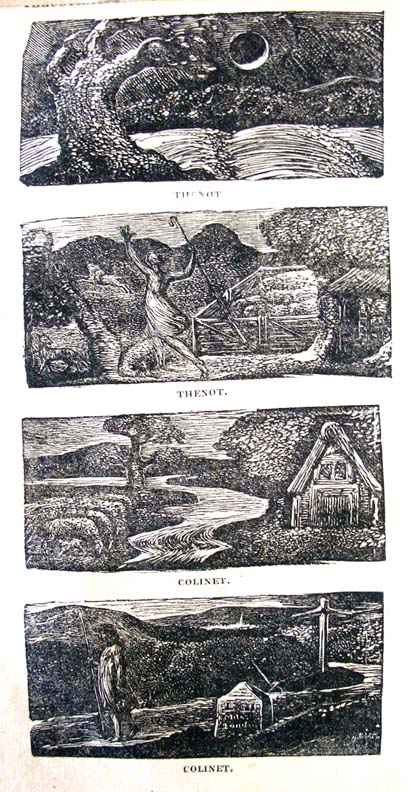

Princeston University Library The Pastorals of Virgil, 1821 Proof sheet printed by Blake |

Here is a quote about Blake's illustrations to Thornton's Virgil (1821-21) from William Blake, by Martin Butlin, published by the Blake Trust:

"The impact of these exquisite designs is best expressed in the words of Samuel Palmer: 'I sat down with Mr. Blake's Thornton's Virgil woodcuts before me, thinking to give their merits my feeble testimony. I happened to think first of their sentiment. They are visions of little dells, and nooks, and corners of Paradise; models of the exquisitest pitch of intense poetry. I thought of their light and shade, and looking upon them found no word to describe them. Intense depth, solemnity, and vivid brilliancy only coldly and partially describe it. There is in all such a mystic and dreamy glimmer as penetrates and kindles the innermost soul, and gives complete and unreserved delight, unlike the gaudy daylight of this world. They are like all that wonderful artist's works the drawing aside of the earthly curtain, and the glimpse which all the most holy, studious saints and sages have enjoyed, that rest which remaineth to the people of God.' The designs had an over-whelming impact on Palmer's visionary works of the Shoreham period and also on the engravings of Edward Calvert." Page 138

The curator of the British Museum writes:

"Introducing Blake's illustrations to Philips's eclogue Thornton writes that they 'display less of art than genius', although he also boasts that they are by 'the famous Blake'. Certainly, Blake's wood engravings were extremely unconventional: they were also clearly more artistically ambitious than the numerous other illustrations in 'Pastorals of Virgil'".

Dr Thornton would have done well to read from Blake's Descriptive Catalogue to learn that the visionary artist is representing realities unseen by the 'mortal perishing organ of sight' which sees only 'a cloudy vapour or a nothing'. To the artist the imagination is the visionary eye through which spiritual existence is made known. The image he produces conveys the lineaments of the object represented, not the superficial appearance. Unless the viewer sees through his imagination to the underlying spirit which is animated, the picture is nothing but a misrepresentation of nature.

Descriptive Catalogue , (E 541)

"The connoisseurs and artists who have made objections to

Mr. B.'s mode of representing spirits with real bodies, would do

well to consider that the Venus, the Minerva, the Jupiter, the

Apollo, which they admire in Greek statues, are all of them

representations of spiritual existences of God's immortal, to

the mortal perishing organ of sight; and yet they are embodied

and organized in solid marble. Mr. B. requires the same latitude

and all is well. The Prophets describe what they saw in Vision

as real and existing men whom they saw with their imaginative and

immortal organs; the Apostles the same; the clearer the organ the

more distinct the object. A Spirit and a Vision are not, as the

modern philosophy supposes, a cloudy vapour or a

nothing: they are organized and minutely articulated beyond all

that the mortal and perishing nature can produce. He who does

not imagine in stronger and better lineaments, and in stronger

and better light than his perishing mortal eye can see does not

imagine at all. The painter of this work asserts that all his

imaginations appear to him infinitely more perfect and more

minutely organized than any thing seen by his

mortal eye. Spirits are organized men: Moderns wish to

draw figures without lines, and with great and heavy shadows;

are not shadows more unmeaning than lines, and more heavy? O

who can doubt this!"

No comments:

Post a Comment